Sustainable transitions are needed in business and investment practice to head off coming poly crises and build a prosperous future for the growing global population.

But plans for such transitions are few and far between and often lack credible substance to bridge the link between ambition and action. Indeed, many appear to rely upon an unspecified magical transformative ingredient that will make it all happen – a problem also experienced by South Park’s underpants gnomes.

This article highlights how action can lag the rhetoric of some sustainable transition approaches and explores the essential components of a plausible plan.

OK I understand sustainable transition – so what are underpants gnomes?

Underpants gnomes appeared in 1998 in the infamous South Park animation series. Since then they have been used as a concept to explain problems in everything from political economy to healthcare and sports team strategies.

Underpants gnomes lack the magical ingredient required to turn the initial intention – underpants collection, into the desired outcome – profit.

Without clarity on phase 2, profit will not be realised.

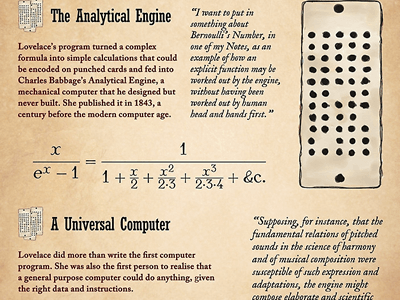

South Park’s underpants gnomes aren’t the only example of satirising intentions and outcomes without credible plans, Sidney Harris’ 1977 cartoon for the American Scientist showed two professors looking at a blackboard full of complicated mathematics, with a box in the middle saying “Then a miracle occurs”, and a comment underneath “I think you should be more explicit here in Stage Two”.

But what do either underpants gnomes or poorly articulated miracles have to do with sustainable transition? A lot. Sustainable transition is the order of the day, the idea that, to meet and overcome the challenges of the climate and nature crises, accelerating inequality and ecological overshoot, we need transformations in both systems of value and systems of production. These require fundamental changes in the behaviour, performance and impact of investors and companies, especially those with the most significant impacts.

Sustainable transition is exposing the gaps between aspiration and action

The recognition that global challenges require fundamental changes in the functioning of capitalism is slowly taking hold. But will this lead to the changes required, or just yet more ambition without meaningful action?

For example – GFANZ (Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net-Zero), founded with great fanfare in 2021 at the COP 26 climate conference has 550 financial institutions as members, comprising the world’s biggest banks and investors, theoretically committed to reaching net zero by 2050, but also to the 1.5°C target, and to taking immediate action to halve emissions by 2030.

Yet despite members’ theoretical commitment, real action is proving harder to see. Set against the absolute need to contract and shift investments from coal, oil & gas into renewables. GFANZ members have been observed to be continuing business as usual, pouring investments into fossil fuel expansion.

Carbon Tracker research backs this up, noting that European majors Eni, Shell and TotalEnergies have published plans to reduce production, but they fall far short of what is required for a 1.5°C pathway. All three do commit to reducing oil production but also plan to increase gas production. Carbon Tracker calculates that TotalEnergies’ global production will be 13% higher in 2030 than in 2019.

The more cynical amongst us (and to be working in sustainable development necessarily requires a healthy dose of cynicism) might suggest that such initiatives are really intended as a smokescreen for inaction. However, it is probably (and more charitably) fair to say that the intentions of groupings such as GFANZ, and many other big-ticket collaborative endeavours are inherently well-meaning. They just tend to founder on the inertial realities of corporate policies and an economic system which treats transactions as positive, no matter what they transact, and treats the environment and society as free goods.

All systems have in-built inertia and status quo bias. Investors and companies are no different, for years they have been rewarded, by shareholders, regulators and customers, for certain behaviours. It can be difficult to recognise that these behaviours are now unsuited for a changing world. Of course, there is still plenty of money and social reward to be gained from unsustainable activities.

This all means that many collaborative initiatives (and I have been involved in a few), even those established with the best of intentions, can struggle when hard decisions are required to change the direction of travel and avoid being mired in an incremental improvement to business as usual.

What makes a credible sustainable transition?

Whilst the science of climate change and many other sustainability issues can be complicated, the fundamentals of corporate transition are relatively simple:

- Recognise the areas of priority, purpose and performance that need to change.

- Make plans to support change.

- Understand how you will measure change.

- Start working on the actions you have planned and consistently disclose progress.

- Realign when you are off course.

- Be accountable and transparent.

However, there has been concern about the quality of the transition plans that do exist. CDP’s recent analysis Are Companies Developing Credible Climate Transition Plans? found that while 4,100 organisations had developed a 1.5°C-aligned climate transition plan, only 81 reported sufficient detail to 21 key indicators in CDP’s questionnaire that align with what the organisation considers to be credible transition.

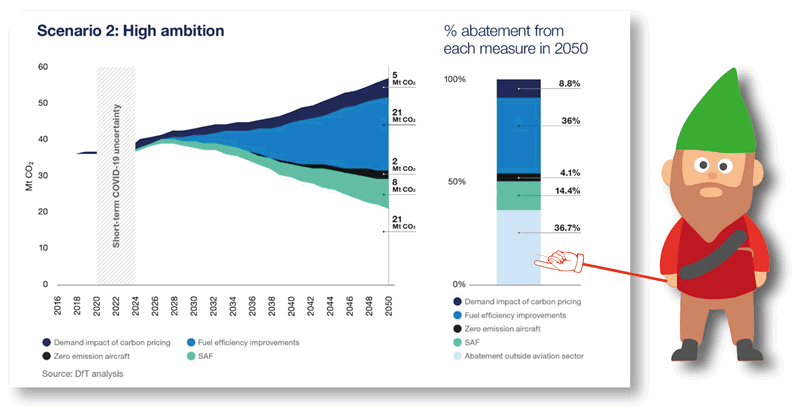

(2022) UK Department for Transport

From planning to delivery

The challenge is not how to plan, but how to deliver, and whether companies setting transition plans will follow through on stated intentions.

The basic elements of corporate transition plans are relatively well known and are generally the same for different types of transition, whether for Net Zero or for other purposes.

Credible plans require:

- Clarity on what activities will cease.

- How decline in will be managed in some areas of existing business.

- How capex, R&D and innovation will be shifted into areas that need to grow to meet the requirement of sustainable transition

- How short to medium-term financial impacts will be managed.

- The case for reinvestment for investors and stakeholders.

Credible (investor and stakeholder) responses to such plans would necessarily require:

- The real time withdrawal of capital from company activities whose plans are not in line with climate transition.

- Significant credit risk adjustments in those companies whose actions are not in line with climate transition.

- Firmer mechanisms to require membership of initiatives such as GFANZ to deliver change in performance, not just signatures.

- A total and immediate ban on any hint of underpants gnomes.

Capex and innovation – unsustainable funding for a sustainable future?

It will not always be summer; build barns.

Hesiod

Financing sustainable transition is a major obstacle to progress. It is often argued that the means to fund fundamental change must be generated by the very activities which need to be phased out.

This argument is often used in hard to abate sectors (carbon intensive and fossil fuel dependent). However, in practice there is little evidence of preparation or investment in radical change.

For example, Carbon Tracker’s recent Paris Maligned report, found that the capex (capital expenditure) spending of oil and gas companies was completely misaligned with any potential global 1.5°C future: “In total, 62% of our universe of 52 companies had sanctioned new projects in 2021/Q1 2022, with 40% approving assets we assess as being inconsistent with a well below 2°C scenario”.

Reclaim Finance’s recent research states even more starkly: “Despite being very vocal about its growing investments in renewable energy, the European oil and gas industry dedicates only a small part of their investment to renewables. In the short term, the six European oil and gas majors plan to spend 60% to 90% of their investment capacity in oil and gas.”

Another way of assessing the readiness and capability of institutions to undertake radical climate transition is to look at patents held as an indicator of an ability to deploy innovation. In MSCI’s ESG and Climate Trends to Watch for 2023 the patents held by the energy sector as a whole, and of some specific oil and gas companies, are assessed. The analysis found (p. 50 of the report) that patent holdings for the largest companies were very narrow, “…the largest concentration of patents complemented the traditional activities of fossil-fuel extraction.”

A lack of guidance is not the problem

Ironically, given the criticism above about the current performance of a number of GFANZ members, the institution itself has produced some of the best materials defining and supporting assessment of sustainable transition. Their Expectations for Real Economy Transition Plans represents, for example, an excellent resource to guide companies in planning, organising and delivering performance transition.

There is plenty of other guidance out there for companies wanting it, from Planet Tracker’s guidance for credible climate transition plans, the IIGCC’s Investor Expectations of Corporate Transition Plans: From A to Zero, the Transition Plan Taskforce’s guidance to our own extensive guidance on sustainable strategy.

For a useful, high-level overview of some of the characteristics of sustainable transition, see this piece I co-authored while at WBCSD – Business and finance must both work together to build a pathway to a successful sustainable transition.

Challenges to sustainable transition

Despite the existence of a range of guidance to support transition planning, sustainable change is defined by action, and whether companies setting transition plans really intend to make the changes to business as usual necessary to meet their stated ambitions.

Alternatively, it may be viewed as too difficult to make early moves within current economic structures.

Therefore, its useful to consider why we are not seeing enough plans or behaviour aligned with stated ambitions. There are multiples challenges or obstacles to progress which include:

Behavioural and Psychological

Group/corporate behaviour and that of leadership figures is complex. Status quo bias (and other biases) make it hard for different possible futures to be conceived and cultural self-image can also constrain transformation. In addition, it is quite possible that, despite a notional commitment to change, there is little actual organisational intention to undertake the fundamental changes to business as usual that sustainable transition would require.

Technical/Technological

Many of the most carbon intensive industries require dramatic changes in business activities or models. This is uncharted territory, and the technical and technological challenges are considerable. They will require investment in innovation and R&D to support (in some cases) exponential scaling of emerging technologies and approaches.

Financial

Whilst there have been significant shifts in how financial system actors have engaged with the need for sustainable transition, there remain practical challenges for more sustainable intentions to be recognised by conventional accounting and valuation processes.

These include:

- Peer comparison – investors make comparative judgments on corporate performance and intentions, if an oil and gas company is making money now, then mainstream analysts may struggle to justify not holding stock.

- Time horizons – the period over which an investment decision is made is frequently misaligned with the manifestations of climate or other sustainability risks, meaning that whilst a longer-term challenge is apparent, shorter-term impacts are harder to articulate and translate into the financial metrics required for investment decision making.

- Many of the impacts are external – accounting and valuation processes still struggle to recognise and prioritise unpriced or under-priced impacts, meaning that decisions are largely still made using conventional financial metrics.

- Policy remains inconsistent and contradictory – a lack of clarity and consistency in regulatory policy means that decision making for more sustainable investment can be risky and uncertain.

Economic

Valuing the future term has long been the Achilles heel of economics, which prioritises present value over potential future value, and consistently discounts future value. Global environmental and social challenges have tended to be treated by economics as inconveniences to market theory rather than challenges to its very continuation.

Sustainable transition is at the heart of such fundamental challenges as they require a shift in valuation and incentives that prioritise behaviours likely to deliver transition and to appropriately value the business and technologies of the future.

In the long-term carbon intensive businesses will not be viable – but they currently are, because carbon intensity is not yet considered a significant enough indicator of a business’s likelihood of failure.

In the absence of significant regulatory intervention, the main driver is market sentiment and collaborative polices/targets which are mainly socially driven. Price signals still support unsustainable activity.

Pre-emptive decision making in corporate leadership

Decision making in corporate leadership is key here. Significant corporate change, though sometimes driven by the power and vision of specific individuals, frequently follows near disaster or collapse. Yet studies of pre-emptive transformation demonstrate that acting in advance of potential disruption is more likely to succeed. To state the obvious – acting in advance of disaster is better than trying to recover from it. Boston Consulting Group’s analysis identified several success factors for successful transformation (which echo the elements noted above):

- Above-average capital expenditure.

- Above-average R&D spending.

- Long-term strategic orientation.

- Leadership change.

- Above-average restructuring costs and a formal transformation initiative.

Magical thinking or necessary aspiration?

It is easy to be disheartened by the apparent intent of capitalism and the institutions within it to accelerate us towards Suicide by Planet. Simultaneously appearing to commit to radical change whilst seeming to undermine the possibility of that change ever taking place.

The penalties for humanity for not delivering change are difficult to overstate.

However, the penalties within our current economic system are either weak or absent. The paradox being that potential damage is still largely treated as an externality, too uncertain or too far in the future to be considered.

But it isn’t without precedent to commit to ambitious targets without knowing quite how we might get there. Humanity has shown that, through examples like the moon landings, and the global agreement to tackle the hole in the ozone layer, that it can meet targets or attain change that seemed unlikely or impossible.

The challenge for sustainable transition is that, unlike the race to the moon, where ambition was matched with activity, too many initiatives lack a fundamental alignment between intention and action.

This will often be difficult. But waiting for the underpants gnomes to save us is not an option. Magical thinking is not investible. Plausible plans, utilising provable and scalable technologies are.

The challenge for investors, and other stakeholders, is to be able to tell the difference between the two and reward the realistic and realisable.

developing strategy / Making plans

Can we help you?

We help companies, charities and NGOs navigate sustainability trends, risks and challenges and build or improve strategies, approaches, and plans. They want to develop and meet ambitious objectives, reduce footprint and enhance value – we provide support them to help achieve that.

DISCOVER MORE | Sustainability Issues

Avoiding strategic greenwashing – why your business strategy must be plausible

Avoiding strategic greenwashing – why your business strategy must be plausible

Leave a Reply