“What is a sustainable product?”

This is a question I’ve been asked by clients twice in the last month, alongside the related question “Is there a standard definition of a sustainable product?”

The simple answer to the first question is:

“There isn’t one at the moment – but we can describe what it should look like.”

And to the second question “No”.

These are deceptively simple questions but an essential part of sustainable business strategy. There are several aspects that must be picked apart to answer them. So, I’ll do that bit by bit.

What does sustainability even mean?

Many companies employ different interpretations of what sustainability means. Sometimes this is to manipulate consumer attention (or the facts), but also because different things are important in different contexts and value chains.

There is not a single of standardised definition of sustainability either, but the closest is the Brundtland Commission’s (1987) definition of sustainable development.

“…development which meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.”

This is disarmingly simple – but also requires some work to really understand it.

In simple terms sustainability means doing/producing/developing products, services and activities that meet people’s needs. However, the crucial dimension of time is introduced to accommodate the aspect of future generations – that having an eye on the opportunities available in the future is something that should be of priority now.

This is where the aspect of doing no harm comes in, because it’s not possible to meet current or future needs if environmental or social harm is caused. There is also a strong component of equity. Equity is not explicitly in the Brundtland definition, but when you look deeper into “meeting needs”, and personal and societal development, you realise that this can’t be done without addressing the following question “how will our choices of today allow people in the future to have wider rather than narrower choices?”

Do no harm sounds like a very low bar, but in fact it’s currently very difficult in most circumstances. This is largely because sustainability aspects have historically not been important criteria in the way we design industrial processes, products or services, commercial relationships or economies.

Generally speaking, being sustainable (or selling a sustainable product) is not currently possible – at least while most industrial, transport and economic systems remain unsustainable. Some companies and products are getting closer, but if you want any significant scale it becomes challenging as you rely on wider infrastructure. For example, you could produce a very low impact product locally but still rely upon ‘dirty’ logistics systems to deliver them to wider markets.

What does ‘sustainable’ mean in common usage?

In everyday language ‘sustainable’ has become synonymous in practice with:

‘relatively less unsustainable ‘

or very simply:

‘less bad’

or (comparatively speaking) the:

‘best option/ least worst option’

None of which sound very positive, marketable or that impressive given the big brains we humans like to parade around.

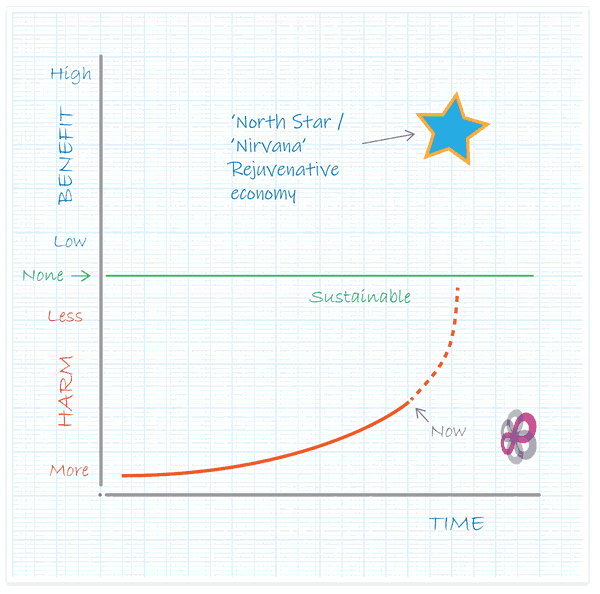

Strictly speaking, looking at the diagram above, we’re in the ‘harm’ zone now and trying to move towards the line of sustainability where no harm is done and we can begin to look at positive contributions from products and services to provide rejuvenative effects.

This model is of course a simplification. Many of the least unsustainable products at the moment have minimised their impacts and also have positive environmental or more often social/economic aspects.

How do we improve …

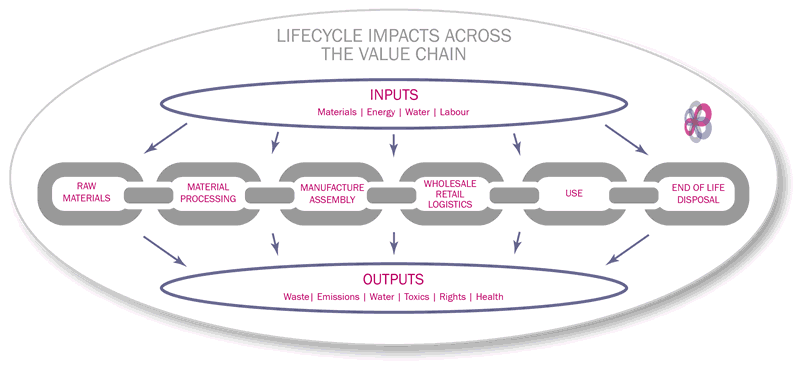

While sustainable products largely remain an ambition, we can however describe the characteristics of a sustainable product. These characteristics/principles must be applied to all stages/aspects of the value chain – and over time. So, it must apply to materials sourcing, manufacture, wholesale/ retail, distribution, product use and product end of life/disposal. Many management theory/consultancy value chain models tend to ignore or under emphasise either end of this chain.

It is at these ends where most of the impacts and risks reside.

What does a sustainable product look like?

A sustainable product would use…

- Raw materials made of abundant and renewable materials (this can be naturally abundant or technically abundant [a scarcer resource managed carefully/in a circular manner] materials.

- Be made from materials, processes and energy that are safe and clean. That means not giving rise to pollution and/or greater concentrations of toxic, persistent, or problematic substances – like greenhouse gases (GHGs), heavy metals etc.

- Be made using labour and human inputs in ways that don’t give rise to abuse of rights, injury or harm to humans, life and societies in use.

- Use raw materials/processes/activities that don’t significantly degrade the natural environment through pollution, disturbance, damage, extraction or excess water use.

- Be durable and long-lasting in use. This includes reliability and ability to maintain and fix in practice. For example, ifixit (https://www.ifixit.com/) campaigns for electronic products to be easily mendable in practice.

- Use and support economic activity and relationships that do not drive, support or reinforce dependencies or economic subsidies from poorer to richer, undermine social equity, or degrade health, competence or individual/personal rights and sovereignty.

What does this mean in practice?

Most if not all currently available products are not sustainable.

This of course leads to confusion as companies don’t want to market their product as ‘marginally less damaging than product C’.

Therefore, some companies will claim products are sustainable when they hit some of the principles above in some way. In absolute terms products may not be sustainable – but they can be on a path towards it.

How can companies describe sustainable or preferable aspects and what tools/approaches may feature?

- Products are mostly described in terms of lower impacts and characteristics/methods used to achieve that.

- ‘Circular’ (circular economy) is a generally a tool/model to reduce virgin material use and or drive efficiency (using less of a problematic thing to reduce impact). The concept is to develop circular rather than ‘linear’ patterns of resource use. In practice this often means a more holistic or systematic approach to re-use or recycling.

- Renewable materials/energy – reducing impact in upstream processes.

- Efficiency – products that consume less energy in typical use and therefore reduce overall impacts – for example electric cars.

- Social auditing of products/services – to try and measure/maintain and promote social standards of behaviour or performance, for example decent working conditions and/or pay. For example, Fair Trade.

- Green Chemistry – designing out toxic/problematic/persistent substances. This reduces production impacts, makes for safer products and creates fewer end of life/disposal problems.

Benefit claims

Some or all of the above approaches may be used in a given product. Many products will therefore include claims on positive performance of one aspect or more. Theoretically this can move beyond ‘doing no harm’ into a positive contribution to the environment or society. In many cases these are valid – but they will contribute to part of the balance against negative aspects.

Claims for a product to be sustainable when only some of the issues and impacts involved in its manufacture, use and disposal are covered is called greenwashing (there are several other flavours of this too).

Case study – is this a sustainable product?

While writing this article the advert below appeared in my FB feed. WWF UK’s face mask claims to be 100% sustainable – is that possible?

Verdict

Amongst available options there’s a strong and defensible argument that WWF’s facemask minimises the majority of impacts associated with a typical face mask product.

However, it’s not impact free. Organic cotton is produced the other side of the world and has significant land use and water impacts. There will be transport/logistics and waste impacts in the supply chain. Together with the impacts for use (energy, water, detergent) the overall lifecycle impacts could be greater than a synthetic alternative.

Is it 100% sustainable – no (just like 99% of all other products).

How do I design a ‘sustainable’ product?

Expectations are changing and people are demanding that the products they purchase and feel proud to own or use meet their own values – or at least don’t noticeably undermine them.

As can be seen from the example above, all options have some positive and negative aspects and a number of trade-off choices have to be made in design and manufacture stages.

If you are designing a sustainable product your goal will be to remove or reduce negative aspects and maximise the positive ones.

The more comprehensive and wide-ranging approach to all issues/aspects across the value chain the better.

How do I buy a sustainable product?

The most sustainable product is the one you don’t buy.

This was highlighted famously by Patagonia’s ‘Don’t Buy This Jacket’ campaign from Black Friday 2011.

This not only headlined with a message to not purchase, but also highlighted the negative aspects/impacts of producing the jacket – and this from a company working hard over time to reduce those impacts.

The next best option is re-using a product to get additional utility from it, followed by choosing a product that deals with all issues across the value chain as well as possible.

This is the space that manufacturers should be seeking to be in.

A complex picture

Like all things ‘sustainable’, product sustainability is complex. Perhaps some of the most important messages relate to the journey towards sustainability.

If you’re interested in developing (or assessing) product sustainability what are the key factors?

1. The product design and development should attempt to systematically address all material (as in materiality / priority) social and environmental aspects across the value chain.

2. This is difficult and can be complex. It will also involve trade-offs. Not everything will be with a company’s control or influence – therefore it’s essential to be:

3. Honest, transparent about your claims and the product’s performance and credibility.

4. Sustainability has to be a journey as well as an endpoint. You don’t have to win, but you should make credible and demonstrable progress.

If you're looking to cut through the noise and become more sustainable book a free Strategy Call or simply a Chat

Book a Free Chat or Strategy Call

Driving change in a crisis – can we do it?

Driving change in a crisis – can we do it?

Leave a Reply