‘He who sups with the devil should have a long spoon’

Proverb

Reputation is widely regarded as one of the most valuable assets of an organisation and sustainability can also be an important contributor to both reputation and several dimensions of business value.

This article explores the different dimensions of reputational risk, considers how it can be affected and how you can protect it.

What is reputation risk?

Reputational risk is the possibility of damage to business value if stakeholders think behaviour, actions or performance have fallen short of expectations.

Change in perception of company reputation can follow different kinds of events or drivers, such as poor performance of a product or service, negative outcomes and impacts from operations or a lapse in legal or ethical behaviour/association with unethical practices.

Reputation is driven by a combination and congruence (or incongruence) between what companies do – their actions and real impacts – and what they are saying. Failures in procedures are typically viewed less harshly than intentional acts by a company or its staff.

The topic has been brought into sharp focus in recent years as some environmental activists seek to pursue their objectives through strategic litigation (particularly in climate change related litigation) or by condemning organisations through their associations with other organisations and activities which are considered to be unethical or significantly unsustainable.

The business of business is business?

When businesses took little responsibility for their actions beyond the legality of an activity or transaction, perhaps times were simpler.

However, the activities and impacts of business raise a complex range of ethical questions. While there are many areas of common ground and consensus, ethics are inherently value-based, qualitative and the subject of varied opinion and perspective – what might be considered legal and legitimate activity or behaviour by one person may be seen as unacceptable and exploitative to another.

So, in today’s complicated business landscape, how do you navigate the possible hazards and make sensible decisions?

Who are the stakeholders – who cares?

Damage to reputation can affect both short and longer-term financial performance, but which are the stakeholder groups whose actions and perspectives can affect reputation?

Key stakeholder groupings can be:

- Existing and prospective customers.

- Partners and suppliers and how they engage.

- Employees and prospective employees.

- Investors, analysts and ESG rating agencies.

- Suppliers and vendors.

What are the risks?

Damage to reputation can impact revenue, market value or brand.

Such damage stems principally from a loss of trust and confidence in the organisation and/or a weakening in expectation or belief around the ability of the organisation to deliver on financial and non-financial goals in the future.

Events that result in reputational damage tend to give rise to losses that are far larger than the initial direct cost of the event. The table below categorises and outlines some of these risks.

| RISK TYPE | EVENT OR DRIVER | PARTICULAR SUSTAINABILITY/ESG DIMENSIONS |

|---|---|---|

| Market risks | Poor earnings or income shocks | Unsustainable business models, stranded assets |

| Poor commercial investments or transactions | Buying or partnering companies with controversial activities | |

| Operational risks | Underperforming/poor products or services | Poor environmental or social performance coming to light |

| Data breach, loss of customer data | Poor governance, loss of trust | |

| Poor treatment of employees, suppliers | Particular risks in longer/riskier supply chains | |

| Fraud or bad financial practice | Indicator of ethical practice | |

| Regulatory infringement | All instances – but can have specific social/environmental aspects. Greenwashing. | |

| Ethical risks | Any of the above aspects coupled with bad intent/unethical behaviour | Includes communication risks like greenwashing |

| Unethical practices or behaviours, market manipulation, fraud, bribery, corruption | Ethical considerations are an important part of responsible business practice | |

| Third-party relationships – association with unethical behaviour in customers or suppliers | Association risk is becoming increasingly important | |

| Poor governance allowing space for bad actors | Often third parties in the supply chain with insufficient scrutiny/control | |

| Misleading communications on company performance, products or services | Companies get into trouble for greenwashing when they highlight good news in a small or sub-strategic area of their business |

Taking this into account, what are the most dynamic or growing risks?

In terms of prominence (this may of course not translate to greatest impact) there is currently a large, noisy and vociferous debate around association risk – risks from being associated with behaviour/brands considered unethical. This causes confusion and uncertainty around who companies should or should not engage with.

Business activism

In recent months this has been brought into sharp focus in the creative industries with increasingly vocal activism focussed on the role of creatives in advertising and marketing in supporting and facilitating companies contributing to the climate crisis – specifically oil and gas companies.

The Clean Creatives initiative’s members have pledged to ‘cut ties with fossil fuels’. What does that include? You can see Clean Creatives’ list here: https://nofossilfuelmoney.org/company-list/

The Clean Creatives pledge commits agencies, creatives, and strategists to refuse any future contracts with fossil fuel companies, trade associations, or front groups. The entities covered by this pledge include:

- Companies whose primary business is the extraction, processing, transportation, or sale of oil, gas, or coal

- Utilities and Electric Cooperatives that meet one or more of the following criteria:

- Generate 50% or more of their electricity from fossil fuels

- Generate 50% or more of their revenue from business in fossil fuels

- Play an active role in funding new fossil fuel infrastructure

- Trade associations or other industry-funded nonprofit groups representing the interests of these companies, utilities, or cooperatives

- Any new entity meant to advance the message or goals of the above companies or groups, while obscuring or hiding their financial contributions.

How does this play out in practice?

To take a current example, it’s been widely reported that Havas has won the account from Shell for global B2C strategic media buying, allegedly worth $27M.

This decision has been widely criticised, particularly by groups including Clean Creatives and Comms Declares.

Red Havas, a subsidiary, has allegedly lost a contract from the Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty Initiative because of this move.

Additionally, four Havas subsidiaries are currently B-Corp certified (London, New York, Lemz and Immerse). Campaigners are using that lever to question Havas’ membership of B-Corp and apparently have requested a review by B-Lab as part of its complaints procedure.

However, it’s more complicated still, the Havas owned Tripkt agency is itself a member of Clean Creatives.

So, Havas has a communication challenge on its hands, but this is not unique. All the major global agencies have similar relationships and have also been criticised. So what are the wider implications in play?

“Advertising is only evil when it advertises evil things. Like Shell, or pop tarts.”

David Ogilvy

The extension of identity politics

Superficially Clean Creatives’ objectives are clear. They don’t want to support oil & gas and are building a wider movement to limit (or if wildly successful block) access to advertising and marketing services.

Many people can get behind that aim.

The challenge is that the world is far more complicated than this. We are all (explicitly or implicitly) dependent upon oil – whether we want to be or not. Many people, me included, want society weaned off this dangerous (but very useful if you ignore the side effects) product as fast as possible. There are strong arguments that the oil majors are dragging their heels and delaying an inevitable transition to a low carbon economy.

But how do you develop principles on where to engage and where to avoid engagement when the world is so complicated?

I researched some sentiment on LinkedIn while writing this article. One commentator suggested that as individuals we should stop buying oil-based products – petrol, plastics, pharmaceuticals. That’s not easy, fossil fuels and derived products are fundamentally woven into society and our economy, so disassociation is currently largely impossible, especially if you include other essentials that are currently dependent upon fossil resources – like food.

What is perhaps new here is the greater concentration on guilt by association.

This means that the debate is further polarised, leading to pass/fail binary decision-making. This might support the idea of ideological purity, but it advances the pretence that there are unequivocally ‘good’ choices rather than merely ‘better’ ones available in the world. Surely this thinking is simply just establishing new heresies?

Association risks – who to engage with?

If you are a company wrestling with these issues, how do you decide who to engage with and who to sell your services to?

This superficially simple question masks some complex and rather challenging questions. When you add a dash of tribalism, entrenched positions and deeply held beliefs to the mix, you get a landscape that’s fraught with uncertainty and risk.

In today’s activist society expectations have changed dramatically, but their origins have been there for a long time. As I grew up there were boycotts of South African goods in protest against apartheid, further back still (contrary to what my children believe, that is possible), in 1791 there was a boycott in England of sugar produced by slaves following the failure of parliament to abolish slavery. This apparently reduced sugar sales by over 30%.

In the intervening time, sensitivities have changed further, decades of encouragement for people to act as consumers rather than citizens and the rise of social media technology mean there is a hugely complex landscape, littered with potential hazards.

Exclusionary approaches

Perhaps you can start by not working with companies that are ‘bad’?

Exclusionary approaches have been widely used in ethical, SRI (Socially Responsible Investing) and ESG investments. The approach is used to exclude companies/organisations involved in highly controversial activities. Generally accepted international principles/standards are often used to describe responsible conduct, for example the UN Global Compact (UNGC), International Labor Organization (ILO) standards and United Nations Guiding Principles (UNGPs).

Typically, excluded activities involve:

Arms – manufacture/marketing of civilian firearms, cluster munitions, landmines, nuclear and biochemical weapons

Labour – involvement in forced or child labour

Human Rights – involvement, directly, via their supply chain or in complicity with third parties, in human rights violations

Gambling – significant involvement without harm reduction

Alcohol – significant involvement without harm reduction

Product testing on animals – without demonstrable social/medical benefits

Environment – significant contribution to environmental problems and poor management of risks

Tobacco – manufacture of products.

Product versus behaviour

Looking at the list above there are some activities and products that can trigger exclusion, and others reside in a ‘grey’ area where they might be accepted under some circumstances. For example, tobacco is routinely on blacklists. But there are nuances here. If we look at Robeco’s criteria (https://www.robeco.com/files/docm/docu-exclusion-policy.pdf) we can see that their exclusion criteria are tiered to reflect a consideration of levels of involvement with tobacco:

Tobacco production ≥ 0%

Tobacco revenues from retail ≥ 10%

Tobacco revenues from related products/services ≥ 50%

What does this mean? If you’re a manufacturer then you are excluded, if your retail operation includes some tobacco sales then you will only be excluded above certain threshold levels.

Thresholds

Because the real world is complicated and messy, thresholds can provide a useful and pragmatic way to deal with the balance between relatively minor and significant involvement. Clean Creatives use a 50% threshold for energy generation from fossil sources and SRI investment criteria often use thresholds to allow some minor involvement in activities that are excluded if they represent a significant part of overall business.

This challenge is one of degree – is a relatively small involvement in something negative allowable, and if so at what level do you set the threshold?

Inclusive Approaches

Perhaps you can simply work with companies that are ‘good’?

Positive screening or inclusionary approaches make use of ethical and other ESG (Environmental Social and Governance) criteria. These criteria are often unclear and difficult to quantify, but they form the basis of considerable effort to generate data in the investment / ESG world. They can include looking at carbon or material use intensity, screening business practice against accepted norms, community or impact investing aspects and looking for outperformance in sustainability-related measures.

Inclusive approaches can be a useful part of the toolkit, but they don’t really help you deal with the more difficult, less clear-cut and ambiguous cases.

Reputational Risk – what do you need to get right?

If we recognise the challenges of overly binary thinking, how do we step back from the noise and identify what’s important and where the critical decision factors lie?

Engagement with the world’s most damaging companies is vital – otherwise, how are we going to achieve change?

So when, and how, is engagement valid or useful?

If we look at B Corp’s principles, they tend to take a risk-based approach rather than a rigid exclusionary one. Therefore, they are looking for business to:

comprehensively identify and measure the impacts of their business and improve upon them over time.

And

avoid, manage, and/or effectively respond to specific potential negative impacts associated with specific industries or practices, as well as existing or emergent concerns from their stakeholders.

Companies in high-impact or controversial industries must pass an Eligibility Review. B Lab provides several examples of determinations of these reviews for guidance. Taking the example of fossil fuels:

“Fossil Fuels & Energy Companies (2020)

Fossil fuel and energy companies are disproportionately responsible for greenhouse gas emissions that contribute to climate change. Companies involved in the production and sale of fossil fuels, including those that generate or sell energy derived from fossil fuels, are eligible for B Corp Certification if they are not engaged in specific prohibited practices regarding extraction, lobbying, and financial incentives; have successfully transitioned their energy portfolio to be at least 50% carbon free; and have committed to make progress towards transitioning to a fully carbon-free portfolio within specified timeframes.”

So, in a nutshell, it’s possible to be a B Corp member if you run your business well, avoid some of the most damaging aspects and make a genuine commitment to reducing impact over time (note there’s a threshold here too).

Reputation risks – what needs to be got right?

To manage reputational risks well, organisations require clarity on their strategy, policy, governance, and execution (performance improvement).

Reputational Risk – Key Considerations

Risk-aware strategy and policies

Most larger companies have well-established risk management functions. However, in our experience, they too often focus on traditional/mainstream business risks. While initiatives like TCFD are driving awareness of climate risk, other sustainability-related risk aspects are not always well understood, analysed, or articulated.

Clear governance processes

Top management and the board must be aware of existing and potential reputational risks and ensure that they are adequately reflected in wider governance processes and assessments.

Behaviour intention gap

The gap between stated intentions and actions is important at two levels. At a personal level staff representing the organisation need to follow company policies and processes. This is also important at a company level, where corporate commitments must also be met. In either case, trust can be eroded if there is a gap between intention and behaviour.

Establishing and socialising reputation risk tolerance

This can aid clarity on the actions to take as it is easy to fall into a trap of attempting to avoid all risk. However, it can be very difficult to set a threshold. Some organisations use public trust as an indicator. While this can be useful it is also difficult to accurately assess, and public trust can be erratic and volatile.

Understand stakeholder perceptions and expectations.

An important part of the landscape is understanding where an event or decision may trigger an adverse stakeholder response.

This of course is far from straightforward, but certain aspects are known sensitivities or trigger points. The organisation needs to understand (bringing risk tolerance into play) when its actions may trigger a response – and how important (or otherwise) this response would be.

Many actions can affect public/stakeholder perceptions, but those more closely related to core business activities – or values – are perhaps the most important to consider.

Navigating risk by association

In engagements, assessing association risk requires clarity on what’s involved. While there are many norms, there’s also lots of generalised and sometimes confused thinking.

One important and overriding point is that there are no simple solutions. We are operating in a largely qualitative zone, a messy, complicated, and ambiguous ethical morass. This should be acknowledged.

It is important to achieve clarity on what you are doing and why – on your own terms.

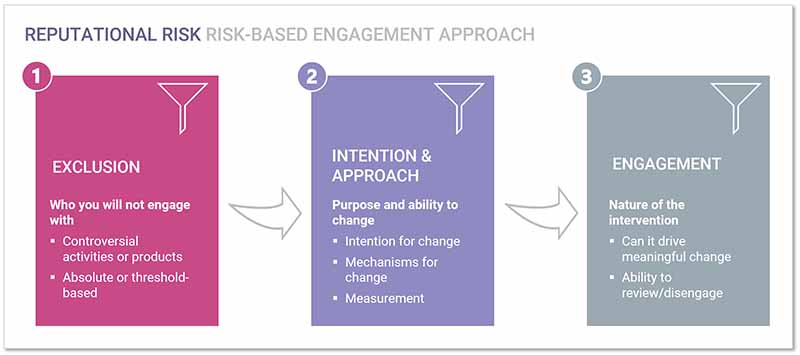

Reputational Risk – Risk-Based Engagement Approach

A sequential, risk-based approach can be useful.

Filter 01 – Exclusion

This step involves identifying types of companies, products or behaviours that you would never engage with.

It might be absolute, or you may set thresholds below which some relatively minor involvement in the activity may be accepted. This list may be short or long for you, and it needs periodic review as it may change over time – especially regarding events related to behaviour.

Filter 02 –Intention and Approach

This filter assesses the organisation’s apparent intention and ability to change, to reduce negative impacts and maximise positive ones.

In this group, engagement is possible if tests are satisfied. This mirrors the approach of B Corp and various ESG investment criteria.

The challenge in these ‘grey’ areas is how do you make a meaningful (and perhaps defendable) assessment?

My contention is the following aspects are important:

Intentionality

What is the stated purpose and intention of the company?

If it has difficult, high impact or controversial activities or characteristics is there evidence that it’s committed to change?

Mechanisms

Change requires intentions, mechanisms, plans and processes. What’s in place, have commitments been meaningfully resourced and tied into management, governance, and performance reward processes?

Measurement

What measurements, targets and indicators are in place? Is there adequate transparency in current and planned disclosure? Public commitments are an important part of this.

Filter 03 – Engagement.

In this step you will assess the specific nature of your engagement.

What is it that you will be doing for the client or partner company?

If it’s in a high-risk category these criteria have relatively greater importance. So, for example if the company’s performance is already good or it has sound plans to improve then a shallow intervention that’s simply promotional might be acceptable. If a company is higher risk, then the engagement may need to be more fundamental in order to meet your tests.

Intervention

Is the work/engagement under consideration something that will help drive positive (in sustainability terms) change in the customer’s core business?

This might be working on core business strategy, developing transition plans or driving efficiencies. Can you make a valid case that your work is helping change the nature of material risks in the organisation you are working for?

Review and Disengagement

Is there the ability to review the relationship and exit if conditions or tests are not met?

Constructive engagement in a complex world

Confidence has long been a critical component of business and maintaining a good reputation has been persistently valuable. While this has perhaps remained a constant, arguably for centuries, the factors relevant and important to business reputation have increased and widened over time.

Changing technology means it has never been easier to share news or opinion and a ‘bad news’ story can spread almost instantly.

But what’s changed most is perhaps attitudes to different actions and behaviours. The rise of consumer activism coupled with aspects of cancel culture make for a heady mix. One that’s difficult to get 100% right.

Clear policies, based upon sound and coherent ethics, good governance and consistent execution will all help contribute to significant risk reduction.

But there remain substantial challenges when the position of your company, or one it wants to do business with, is ambiguous or negative.

If your business is in marketing or advertising, the purpose of the communication is to orient people positively towards a company and help drive sales. In this case the relationship will be inherently tied to and judged by the direction of the associated company and its purpose.

There’s little space to argue for constructive engagement with the businesses that you work with if the basis of your engagement is not actually about creating and driving meaningful change.

If that’s the case you will be judged, fairly or otherwise, on the basis of past and current performance – and the baggage attached to that.

Can we help you?

We’ve worked with companies in the UK, Europe and

beyond to avoid greenwashing by developing responsible engagement and communications approaches, content and copy. Ranging from strategic corporate reporting and disclosure to brand guidelines or in-store packs, we can help you develop content that’s clear, accurate and substantiated.

Book a chat with one of our partners to explore how we might help you – there’s no obligation!

Net Zero Alcohol Strategy *

Net Zero Alcohol Strategy *