The single biggest problem in communication is the illusion that it has taken place.

George Bernard Shaw

To drive change in their organisations, sustainability professionals have to be effective influencers as well as content experts.

However, navigating how to develop the right messages for the right audiences can present a range of challenges, especially when sustainability can be complex, nuanced, and the subject of assumptions and strong passions.

Understanding the nature and types of communication used and valued by different groups, functions and professions in your organisation is fundamental to successfullly communicating sustainability.

Even within a single organisation, ways of thinking, cultural norms and professional perspectives can vary widely. Successful sustainability communication needs to recognise and utilise this diversity.

Types of sustainability communication

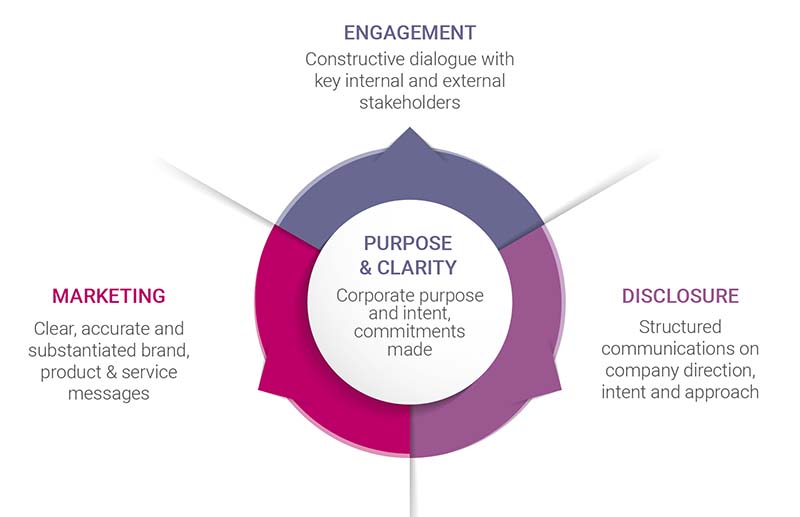

Communication on sustainability is needed in at least three key areas:

Marketing – communicating about your products and sustainability is now often a crucial or valuable exercise. But it’s also important to avoid the trap of greenwashing.

Disclosure – typically includes formal and structured information on company strategy and intent – and evidence of performance.

Engagement – developing and nurturing constructive dialogue with stakeholders both within and outside the company is critical to achieving objectives.

While all of these are important, in this article we are going to focus mainly on aspects that are important for engagement on sustainability – especially within organisations.

What does communication for sustainability need to do?

Communication skills are valuable in most professional roles, but are paramount for sustainability professionals because of the range and complexity of what they typically need to achieve, this can include:

- Broadening understanding and disseminating knowledge – sustainability includes complex concepts and often requires detailed understanding.

- Extending influence – sustainability professionals are frequently either alone or part of small teams – ensuring organisation wide change depends on the help and participation of others from different business functions and activities such as the C-Suite, operations, procurement, brand and marketing.

- Driving innovation – creating understanding and the means by which sustainability challenges and concepts are understood as challenging business as usual and representing vital opportunities for future business change and success.

- Inviting collaboration – sustainability professionals are frequently generalists, real organisational change requires them to harness the insights, energy and involvement of other experts across the business to support buy-in – sustainability should be owned and delivered across the organisation.

- Changing behaviour – sustainability challenges business as usual, if priorities, processes and performance do not change then an organisation will not successfully engage in sustainable transition.

As the list above implies, the requirements for different types of communication give rise to a range of target audiences. Each one will differ in the way that they require, interpret, value and act on (or ignore) information.

These differences arise from a range of factors including individual personality type, background, education, training and responsibility.

Given this, it’s unlikely that a single set of messages can or will be effective for ‘broadcast’ communications across the whole organisation.

This means that different messages are needed for different audiences. Even within these diverse audiences, different groups or individuals may also be best served by tailored communication approaches. So, what might those be?

Different communication processes or messages?

Different people have different motivations, and depending on their personality, profession, and communication styles, the way they receive and interpret messaging can vary significantly.

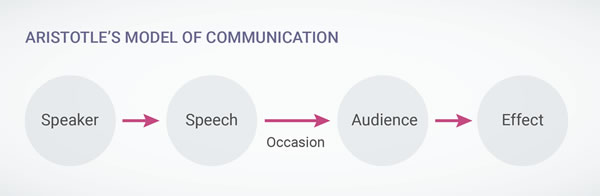

More than 300 BCE Aristotle suggested a model for communication that included 5 elements: Speaker > Speech > Occasion (Target) > Audience > Effect.

Of course, since Aristotle proposed this nuanced way of thinking about specific messaging for specific audiences, there have been many further theories and models describing what might make meaningful communication.

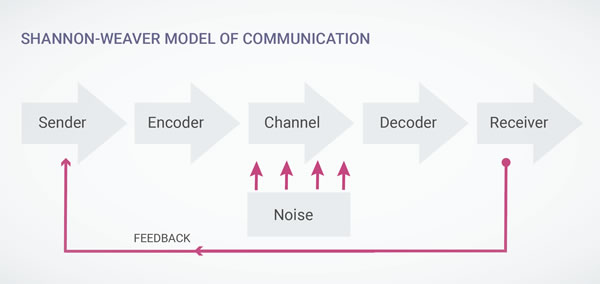

One notable subsequent model was developed by Shannon and Weaver.

This is highlighted below in an adapted form (to include a feedback loop). The Shannon-Weaver model was originally developed by Claude Shannon in 1941 with reference to telecommunications technology, and the noise noted refers to literal electronic signal interference. However, with the input of Warren Weaver the model was adapted to describe how communications of all types are subject to a range of elements which can affect transmission and effective reception.

There are several important aspects in both models, but here we will focus on the audience or receiver.

When facts are not enough

A focus on understanding how different audiences will receive communication requires a consideration of the ways that sustainability messages can be framed and expressed so that they are effectively received, valued, understood, and acted upon.

This means that sustainability professionals need to consider motivations, mental models, information/communication preferences and the professional and personal norms of people they are looking to reach.

Many sustainability practitioners are driven by messages from science that tell them ‘facts’ about the world and how it works. Facts which they believe are powerful enough to motivate others to respond to address issues, challenges and drive changes in business approaches and operations.

However, if sustainable change was as simple as identifying which fundamental scientific truths are relevant in any given situation, wouldn’t we already see a very different world?

The unfortunate truth is that facts don’t always change the world, especially if they are complicated, or present difficult or uncomfortable challenges. The implications also tend to require or imply fundamental changes to common customs, practices or behaviour.

Facts are also not enough when they collide with incompatible values, worldviews, mental models or heuristics.

Part of the problem is our brains. We like to think of ourselves as rational, but our brains have evolved to keep us alive. They are therefore good at processing signals about danger, less good as rational, analytical machines, especially when faced with emergent challenges with long term, uncertain implications. Whilst we might rationalise our decision-making as being driven by logic, in actuality it is frequently significantly affected by bias and emotion, as well as information availability and cognitive overload.

Sustainability Communications – different audiences, different messages

So, if the language of science and the currency of facts are not the whole story, what else is required?

Within our consulting practice, we frequently undertake an exercise to help people think about the messages that are most likely to persuade different target audiences of the importance and business relevance of organisational sustainability.

The results of this exercise are strikingly similar, they tend to demonstrate that the messages that you use to engage (for instance) a colleague are different from the ones that you would use to engage a line manager. Colleagues are more likely to be motivated by messages that reflect values and the role that the organisation can play in solving environmental and social challenges, while line managers want more specific business benefit reasons, like risk management and reduction, cost and resource efficiency and clear bottom-line benefits.

This is of course both a simplification and just plain common sense – people all receive and process information in the context of its importance and relevance to them, which in turn is mediated by their worldview, personalities, and organisational priorities.

One organisation, different cultures

Just as significant for effective communication can be the professional context, norms and cultures of different groupings in your organisation. These can differ widely – to give a couple of examples, think of the difference between colleagues in your finance function and those in your brand and marketing teams.

Whilst the former might be motivated by the extent to which you can translate sustainability into its implications for capital performance and capital expenditure, or how emerging carbon pricing might affect future asset value, the latter will be more excited about whether sustainability means that your company can successfully differentiate its product offering and create brand resonance with targeted consumer and customer segments.

Tuning messages to audiences

Of course, navigating this complexity is difficult, and sustainability professionals are rarely able to either know or have the time to ensure that their every message will be tuned to individual audiences.

However, our experience suggests that a consideration of the following questions will help enhance the effectiveness of sustainability communication.

- Who is my target audience?

- What messages are they used to hearing and how do they receive and process these messages?

- What are the types of messages that they listen to?

- What do they value and what motivates them – what does success for them look like?

- How do they communicate within their teams?

- Do they respond to numbers, pictures, scientific papers, or other methods of communication?

- Do they have specific requirements e.g., one-page briefing, PowerPoint formats, numbers rather than narrative etc?

No silver bullet will magically unlock understanding and engagement for communicating sustainability. However, empathy with your audience, together with an understanding of their situation, communication styles and preferences will help drive the effectiveness of your sustainability communication.

Greenwashing – dimensions of risk

Greenwashing – dimensions of risk

Leave a Reply