“No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main”

John Donne

Is the world a better place because we exist?

Socially useful business is neither a new idea nor one which is particularly at odds with the fundamental conventional purpose of business – to sell things which people want or need.

However, demonstrating social utility has becoming rather a burning issue in recent years, spurred not just by the slow growing questioning of the current mode of international capitalism but also by the rather more pointed challenges to the purpose of whole sections of the economy raised by the recent financial crash.

The topic was the subject of this McKinsey article on business and society and also an exploration session earlier this year, hosted by innovation organisation The Foundation, which asked the question “Socially useful business – Necessity or Nonsense?”

For my answer, I am definitely in the camp of Henry Mintzberg et al when they said “Corporations are economic entities, to be sure, but they are also social institutions that must justify their existence by their overall contribution to society” – perhaps as a direct riposte to the famous quote (attributed variously to Milton Friedman or Alfred P. Sloan) of “The business of business is business”.

Set against the regular mantras of companies justifying their existence by stating that ‘We pay lots of tax’, ‘We employ lots of people’ or ‘We sell stuff that people buy’ there is an increasing groundswell towards requiring a clearer and more detailed demonstration of why the existence of any given company is a demonstrably good thing.

Of course there is a world of difference between ‘We pay lots of tax’ and ‘we pay all the tax we ought to pay’!

The economics of utility

Utility (usefulness, serviceability) has long been a fundamental component of economics. It was at the heart of the neoclassical economic approaches initiated by Thorstein Veblen and before that in the functional utilitarianism (the maximum good for the maximum number) of Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill. Under neoclassical theory, individuals maximise utility and firms maximise profit.

This distinction between utility and profit maximisation within conceptions of economics goes much further back in history to the origination of the very term economics itself. In “Politics”, written in the 4th Century BC, Aristotle discussed two dimensions of activity which are at the heart of today’s perspectives on economics, capitalism and the tensions between common and private good.

Aristotle drew a clear distinction between household management (oikonomia – where the word economics originates) and wealth creation (chrematistica – from the term chrema – a ‘thing’ of which money and wealth is a specific meaning).

Aristotle describes the difference and relationships between the two (in Part IX): “the art of wealth-getting which consists in household management, on the other hand, has a limit; the unlimited acquisition of wealth is not its business.”

Under this description, the process of delivering value creation is a requirement of household management, but not for its own sake “Hence men seek after a better notion of riches and of the art of getting wealth than the mere acquisition of coin, and they are right”.

In their book ‘For the Common Good’ Herman Daly and John Cobb, Jr distinguish between the two concepts further:

“Oikonomia differs from chrematistics in three ways. First, it takes the long-run rather than the short-run view. Second, it considers costs and benefits to the whole community, not just to the parties to the transaction. Third, it focuses on concrete use value and the limited accumulation thereof, rather than on an abstract exchange value and its impetus towards unlimited accumulation…. For oikonomia, there is such a thing as enough. For chrematistics, more is always better… “

Social impact metrics – measuring the symptoms not the disease?

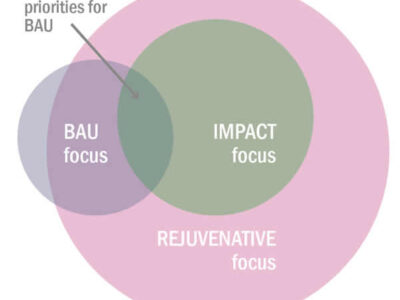

The extent to which the creation of social utility is at the heart of organisational purpose is frequently obscured, often by company activities seemingly intended to create social value.

All too often, the social impact conversation fails to focus upon core business. Instead becoming fixated upon what is done with profits, rather than upon the overall social utility of the business in the first place. Using Aristotle’s distinction – the social dimension of a businesses activities have been interpreted through a ‘wealth-getting’ rather than upon ‘household management’ lens – where the scope of the household is increasingly not only society but also the planet as a whole.

As a personal anecdote, I was once asked to present on climate change risks to the Senior Management and Chair of a large company with significant exposure to such threats, potentially affecting every aspect of its business model. After going through the varied dimensions of the challenges they faced to their business and perhaps, over the long term, their very existence, the Chair thanked me for my input and said that it was important to remember that their ability to invest in such “good works” as responding to climate change was dependent upon generating lots of nice surplus profit by doing business as usual.

This was possibly the most spectacular example of missing the point I had come across for a long time. Yet it is reflective of a key issue in terms of attitude to impact – impacts are those that arise from the existence of a company, not ones that arise from the philanthropic activities, social investment or charitable partnerships of a company undertaken with surplus profits.

Another wonderful example is that of a major company that used its philanthropic funding to secure spaces for school playgrounds and playing fields and proudly, publicly, patted itself on the back. Set against this, the business also generated large profits by being a major player in the public-private-partnerships that gave rise to vast quantities of school land being sold off for housing and shopping developments. Does the former come close to addressing the impact of the latter?

Moving beyond such simplistic, not to say actively disingenuous approaches to demonstrating social benefit is a pressing need for 21st Century businesses. It is no longer enough for companies to say that their legitimacy comes from their existence or from the way in which they spend their spare change, they need to prove their worth to society now and in the future by exploring and demonstrating their fundamental social utility.

Getting to the core of social impact – beyond charity and investment

There is a fast growing range of tools and approaches for measuring social impact, yet the majority of such approaches are designed for charities, not-for profits and impact investors. This means that most attention is paid to spending money in a way that is socially beneficial, not upon the source of the money in the first place.

Going back to the root and purpose of companies and their profits is required.

This is where initiatives such as Shared Value fit in. Moving beyond the tired old narrative of distributing pennies to the poor outside the mansion gates, Shared Value (conceived by Michael Porter and Mark Kramer), is an approach to indicating the intent for and actualisation of economic activity which spreads its benefits to all actors in a transaction, not just some.

B Corps (Benefit Corporations) also seek to demonstrate innate social benefit rather than the after-the-fact conscience-salving that has characterised much corporate philanthropy. B Corp categorises its process as a certification scheme for business, like Fair Trade labels are for products.

B Corp status can only be achieved through processes of assessment of purpose, activity and impact. There are now more than 1,000 Certified B Corps from 33 countries and over 60 industries around the world.

Exploring social utility

Below the level of the structured and detailed approaches of Shared Value and B Corps there is a fundamental and simple question about the social utility of an enterprise: “Is the world a better place because we exist?”

Organisations can further examine their social utility in detail by exploring the answers to the following questions:

- Which of your businesses’ activities provide utility to society (beyond shareholders)?

- To how much of (global) society do you provide utility?

- To what extent does utility provide a wider benefit to people other than direct beneficiaries?

- How can you prove the extent and equity of sharing?

- To how much of (global) society do you wish to provide utility?

- For how long?

- Will your current business model support that wish or prevent it?

An issue of scale

Questions of scale and scope of social utility are critical. For instance, you could make an argument that Hedge Funds are fantastically socially useful for the property market in the West of London, for high-end restaurants and for Lamborghini dealerships as well as providing market liquidity – but would this pass a notional social utility test?

In order to find out, you would have to martial opposing thoughts on the extent to which Hedge Funds also contribute to market hysteria and instability, undermine the strategic purpose of markets, accelerate short termism and contribute towards rising social inequity.

How could these bundles of opposing things be set against each other in order to achieve an understanding of net impact? It is worse than comparing apples and pears, it is more like apples and concrete!

Towards common self-interest

“We are all dependent on one another, every soul of us on earth.”

George Bernard Shaw

Defining and delivering true social utility without getting lost in complex and misleading net-impact calculations requires a more fundamental perspective and approach to assessing the purpose of enterprise in the first place.

The concept of ‘common self-interest’ may provide a solution; the idea that in a massively interdependent world respecting and balancing interrelationships should be a defining theme and design criteria for activity – at the heart of company purpose and activity.

Common self-interest can be expressed as follows (after Arthur C. Clarke), that ‘At scale and over sufficiently large periods of time, private interest should be indistinguishable from common interest’.

The alignment of common and self-interest in the context of a company can be explored by considering the following criteria:

- Interdependency – how reliant are we upon others to conduct our business?

- Inter-subsidy – how is our quality of life subsidised by other people’s quality of life?

- Freedom of choice and opportunity – does our freedom of choice and opportunities depend upon other people lacking their own?

- Diversity and resilience – how do our activities contribute to the capacity and strength of the societies we sell to and depend upon to survive and thrive?

A company seeking to balance self and common interest would naturally need to align its business models and social relationships with the dependencies that represent sources of potential vulnerability and risk to individuals and society over time. A company seeking to enhance its utility would naturally therefore:

- Preserve and enhance natural capital and ecosystem services.

- Focus on the sustainable use of scarce resources.

- Prioritise the use of abundant and renewable resources.

- Recognise social interdependence, prioritising personal and societal wellbeing.

Following this approach is of course, merely harnessing the existing hard-wired drivers of capitalism to a longer term perspective, reinforcing the truth that we all have to live on the same planet and depend up each other for our mutual wellbeing.

A focus upon social utility – to assess and demonstrate the contribution that a company makes to the strength, diversity and well being of society as a whole – is a defining characteristic of the companies that will thrive and shape the 21st century.

DISCOVER MORE | Sustainable Business Strategy

Avoiding strategic greenwashing – why your business strategy must be plausible

Worldwide regulators are tightening up on strategic greenwashing to protect consumers, business and market integrity. As further examples arise there is more, we can learn about what regulators will tolerate and what they require of companies.

Put simply, any leeway for general feel-good …

WEF Global Risks 2023 – What’s new and what’s changed?

While big picture environmental threats of climate change, nature loss and ecosystem collapse remain long term risks, geopolitical instability and the current cost-of-living crisis challenges present emerging challenges to the chance for global consensus and coordinated action.

The WEF (World …

2023 sustainable business trends and challenges – what to watch out for

From avoiding greenwashing to facing soaring business costs, 2023 is set to be a challenging year for most business leaders to navigate.

Regulators, customers and consumers have increasing expectations for good quality, consistent information on sustainability. Communication must be accurate and …

Global Risks 2022

Most major sustainability issues have important risk dimensions for companies – and societies. In many cases these are still not adequately represented in board-level discussion, company risk assessments or registers.

WEF’s Global Risk Report provides a very useful, comprehensive global review and …

Biodiversity – the next crisis?

While we’ve been concerned with action on climate and tied up with Covid19, a larger, related crisis is brewing. Businesses are waking up to the need for action on biodiversity.

Biodiversity is one of many issues organisations should consider when developing (or reviewing) sustainable business …

Transforming the business case for sustainability

In a business context it’s often been necessary to justify why sustainability is important with a business case. While it gets less visibility now, it’s still common to see the symptoms of not having a good business case, or one that’s not widely implemented.

Materiality Matters

Materiality is the difference between a weak sustainability approach and one that’s logical, planned and based upon what’s important. What matters most?

The business case for sustainability – can we make money?

Many people are driven by purpose, the ethical dimension of sustainable business. But all businesses need to make money, we explore where value can be found in sustainable business.

This article was republished by 2Degrees on 30/04/15, Toronto Sustainability Speaker Series (TSSS) Innovation Hub on 29/04/15 and Sustainable Brands on 25/05/15.

I agree 10 per cent – the principle of minimum consensus

I agree 10 per cent – the principle of minimum consensus

Leave a Reply