“There’s no sense in being precise when you don’t even know what you’re talking about.”

John von Neumann

The Final Frontier…how should we communicate the value of multiple capitals?

Who among us can come across a concept called the “Monetisation Frontier” and fail to make a weak and gratuitous reference to Star Trek? Perhaps just me then.

But beyond the sci fi allusions, the concept of a monetisation frontier is becoming more relevant to sustainability with each passing day. Let me explain why.

For years, linking sustainability with concepts of price and value has been the goal of a myriad of initiatives, whether this be in terms of the value of natural environments, the value foregone implications for fossil assets in a carbon constrained world, the value created/ value at risk of work that I among many others played a part in back when the world was young and the new millennium loomed with hope rather than louring with the doom that now faces us all….

There are many dimensions of the sustainability value debate, from the evidence that supports the notion that less unsustainable companies (tending to be termed sustainable or responsible businesses) outperform the market financially (an overview of the evidence for their financial outperformance can be found here) to the efforts to price environmental and social externalities (important things that are effectively ignored by economic and financial activity), to the development of wider notions of value – such as the development of multiple capitals concepts and multiple capital scorecards.

To date, these efforts have failed to stimulate the fundamental change in the nature and purpose of capitalism that they are intended to achieve. The reason why are pretty clear – the scope and influence of such initiatives are dwarfed by the scale of the edifice they are seeking to reform.

Metaphorically, they are like shooting an arrow at a castle wall and expecting the wall to fall down.

Economics and markets are fundamentally founded upon the price signal and the price signal is founded upon the ability of an issue to be monetized. This means that approaches to the integration of externalities that do not give rise to monetisation and therefore a change in the price signal might be fated (unless they are backed up by policy or regulation) to end up merely as potential factors for consideration (perhaps ignored) or aspects which hope to influence either accounting or institutional policies.

In the latter case such signals are by their nature weak as they essentially say ‘I know X behaviour costs $Y much, but if you really should take Z factor into account too!‘ rather than a situation where the price of a thing REALLY reflects its innate sustainability in the first place.

Multiple capitals – narrative or numbers?

“Truth … is much too complicated to allow anything but approximations.”

John von Neumann

The multiple capitals approach seeks to conceptualise a series of value categories in addition to the traditional category of financial capital. The idea is that a consideration of the value derived from other categories – natural, social, human and manufactured capitals – should be integrated within decision making.

However the extent to which such additional concepts of value should be interpreted as literal price signals or more generally as telling us something which should be the subject of policy making (which may in turn give rise to price signals or changed market or investment rules which can be translated into price) is the subject of discussion and exploration at present within the worlds of accountancy, integrated reporting, business and policy making.

A mix and match approach

In the ICAEW (November 2015) paper “Quantifying natural and social capital; guidelines on valuing the invaluable”, Adrian Henriques makes the argument that accounting for multiple capitals should not focus upon a singular approach to description. He suggests that there are three distinct approaches to accounting for value which should and can be used as appropriate to describe capitals values.

Narrative accounting

This is where values and characteristics are described through the development of “stories”. These are intended to provide insight on value and its actual and potential implications, rather than to allow quantification (or translation through to monetisation). Narrative reporting has become an integral aspect of financial reporting. In the UK it is at the heart of the Companies Act 2006, which requires a “Strategic Report”. The Financial Reporting Council guidance on this type of report notes that “The purpose of the strategic report is to provide a company’s shareholders with a holistic and meaningful picture of a company’s business model, strategy, development, performance, position and future prospects.” Shareholders analyse this narrative and make judgements based upon it about the company’s capacity and likelihood of achieving its strategic goals and then assign value to those judgements.

In this context, narrative reporting of multiple capitals can (and to a small extent already is) integrated into an established and recognised approach. Though in my judgement adequate narrative reporting of multiple capitals would require a more fundamental understanding and disclosure of the capitals dependencies and vulnerabilities for a company than is generally taking place at present. The International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) has lead this agenda, placing multiple capital disclosure at the heart of their reporting framework.

Quantitative accounting

Quantitative accounting is more familiar territory for accountants and investors, it concerns the translation of aspects of qualities of capitals in terms of numbers, measurements (of output, profit, realisable utility, demand etc.) which can be analysed in terms of their value implications. Clearly, the methods used to undertake such translation are critical to the outputs which are generated, and can be subject to oversimplification or, more fundamentally, a misunderstanding of the nature of value inherent within a capital.

To take a simple and established example, the value of a forest ecosystem is not just the sum of the market price of its physical outputs such as timber or game. The true value of such an ecosystem is its capacity to produce such outputs plus its wider social (e.g. recreational, health and psychological) and ecological (carbon capture, air, water and soil services, species diversity) benefits.

Another example is a comparison of the relative value of the ecosystem services provided by mangroves versus the economic benefits of conversion of mangroves into shrimp farming in Thailand. This is simply and clearly illustrated in this study published by the World Resources Institute.

Monetised accounting

Monetisation, the translation of qualities directly into monetary unit values (in terms of cost, price etc.). These can then be used to either compare the value of differing courses of action, or (through economic analysis) to drive policy and behavioural outcomes. Rendering complex environmental and social qualities into figures is clearly contentious and potentially morally problematic for the simple and familiar reason that it can lead us to the position of knowing the price of everything and the value of nothing! Nevertheless, monetisation has power (some might say a seductive one) as it fits comfortably into the economic/financial narrative which has become so dominant over the past decades.

Henriques (and Martin O’Connor – see section below on the Monetisation Frontier) notes that such an approach works best when there are well defined and functioning markets for the monetised issue/ service or product. Monetisation without such markets is either pointless or problematic, as it might allow exploitation without adequate valuation.

It is likely that the use of any one of the above 3 accounting approaches to the exclusion of the others will present an incomplete picture of the value of capitals. In his ICAEW paper, Henriques presents a set of guidelines for the use of differing approaches, with an emphasis upon (paraphrased and simplified by me):

- Balance – of differing approaches.

- Participation – of multiple parties affected and interested.

- Relevance – the use of approaches appropriate to their context (e.g. monetisation should only be used alongside the existence of a functioning market).

- Transparency – clarity upon what approach is used and why, what has been left out and which assumptions have been made.

The Monetisation Frontier

“…if people suddenly cleared their minds of this cant of money, what would happen?”

H. G. Wells

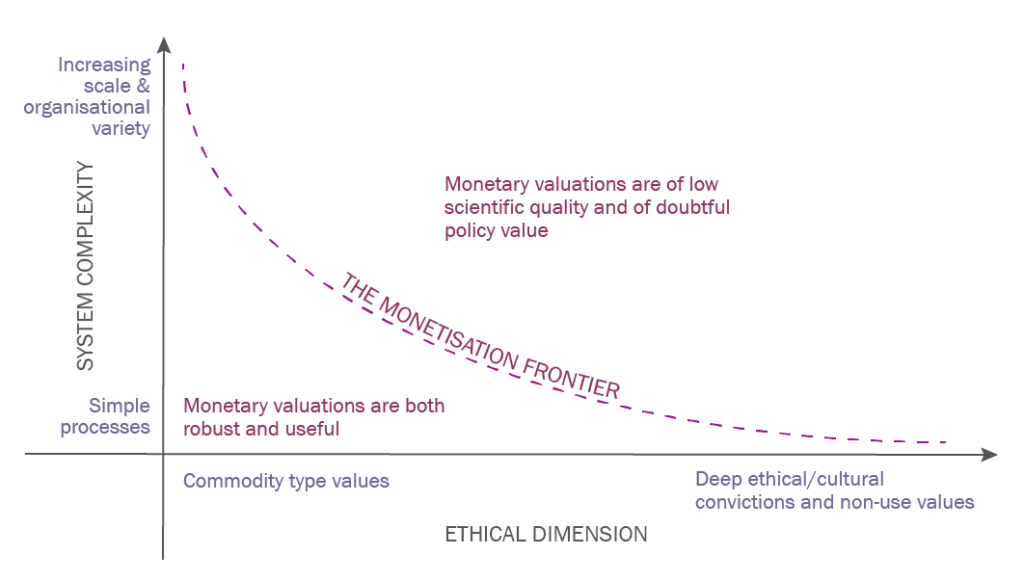

The issue of whether a value concept should be translated into numbers (and price) brings us to the fascinating concept of the ‘Frontier of Monetisation’. Developed by Martin O’Connor and Anton Steurer and first published in International Journal of Sustainable Development (IJSD), Vol. 9, No. 1, 2006 in the article “The AICCAN, the geGDP, and the Monetisation Frontier: a typology of ‘environmentally adjusted’ national sustainability indicators”.

The monetisation frontier is a conceptual approach to categorising the threshold at which a matter crosses from being a policy issue to being a priced one (and vice versa).

The reason this concept is so central to the issue of whether price and value can properly reflect (and therefore drive) sustainability is that the world of sustainability seems rather confused at present as to whether it wants monetisation or not.

The Monetisation Frontier addresses this duality – essentially it considers two dimensions which are fundamental to the point and purpose of trying to translate sustainability into monetary terms:

- The extent to which monetary valuation can be scientifically meaningful, and;

- The policy relevance of monetary figures.

These aspects sometimes seem to be either hidden or forgotten in most discussions – which either focus upon the sacrilege of reducing nature and society to numbers (here is an example from us about valuing your Mother when selling her) or upon the absolute necessity of recognising that everything has to be valued if we are to prioritise it as important.

(The figure above adapted from O’Connor and Steurer. It was downloaded from The Forest of Broceliande, a virtual library of online teaching resources on topics of sustainable development and environmental issues.)

The Monetisation Frontier asks pertinent and still as yet unanswered (or perhaps wilfully ignored) questions about both the utility and desirability of monetisation. It suggests that there are some thresholds at which price monetisation becomes divorced from scientific legitimacy and also those where monetary figures stop being useful for telling us whether a policy is working.

Essentially – monetisation is most effective when it relies upon the lowest levels of generalisation and assumption.

Given both the technical, ethical and knowledge based challenges which it faces, it should be clearly recognised that monetisation is not the answer to the sustainability questions of our time, it is an answer to some of them, but by no means all.

Inputs change or System Change?

“If the land mechanism as a whole is good, then every part is good, whether we understand it or not. If the biota, in the course of aeons, has built something we like but do not understand, then who but a fool would discard seemingly useless parts? To keep every cog and wheel is the first precaution of intelligent tinkering.”

Aldo Leopold

In the Environmental Valuation in Europe Policy Research Brief No. 3 (Series editors Clive L. Splash and Claudia Carter) Martin O’Connor suggests two ways that approaches towards monetisation can avoid the twin pitfalls of price signals either becoming divorced from scientific integrity or meaningless in policy terms.

These are:

- Changing the system boundary – shifting the dividing line between the economy and its external environment by bringing stocks of social or natural capital into economic monetary accounting. This would mean that accounting procedures would focus upon changes in natural capital and value them either from the supply side (scarcity costs, restoration and reparation costs) or the demand side (willingness to pay to maintain the asset).

- Adjusting the economy itself – a primarily policy-derived approach where the sustainability performance characteristics of production and consumption are clearly specified through performance standards. In this scenario changes in natural and social capital states are not reflected directly in monetary terms, but are translated in policy terms which then give rise to monetary impacts.

In essence the two approaches reflect a much wider dialectic that has been at the heart of sustainability price and value debates for a long while. Should we try to translate environmental and social issues directly into price (or price adjustments) or should we redesign the economy so that sustainability value is more fundamentally hardwired into the origination of price in the first place?

I have written extensively on this “choice” between two paths over the last 4 years, and persist in coming down on the side of the latter; that we need to reconceptualise the function and purpose of the economy so that it innately gives rise to sustainability.

However, the former approach – the monetisation of currently unpriced capitals – overwhelming appeals to many, partly because it doesn’t rely upon a redesign of the system as a whole, just an adjustment of its functioning.

This may be more appealing, but will it really deliver the outcomes that our species and our planet requires. Can simple pricing of capitals produce sustainability?

I would say that it cannot, most significantly because pricing complex social and natural capitals is much more complicated than pricing conventional capitals.

In addition to the challenges raised by Henriques and O’Connor there also 2 fundamental reasons why translating multiple capitals into a comparable metric such as money is flawed, not to say impossible within in our current economic model.

1. The dependency challenge

When one capital depends upon another – such as in the case of financial capital (and all others) deriving from natural capital – then reducing each to a number for the purposes of assessing trade-offs ignores the fact they are not equal – that one can only exist with the continued presence and health of the other.

2. The value hierarchies challenge

Fundamental dependencies indicate a value hierarchy. Using a comparable metric like money as a way to put things on a level playing field makes sense, but only up to a point. Such an approach would be fine if the things we were comparing were truly comparable. However, the environment is something we can’t do without.

Revolution through evolution?

The multiple capitals concept, and the intent behind it (to put a range of sources of value alongside the pure financial) is a radical one. If successful it would represent a revolution in economics and finance, and could give rise to a truly sustainable economic system.

However, this revolutionary endgame is currently buried under a rather evolutionary, incremental, approach.

The current economic system is structurally designed (though perhaps not intentionally) to functionally ignore issues of existential importance and therefore is unable and uninterested in driving sustainable behaviour. Its sole success criteria is a de-facto measure of the acceleration of unsustainability (growth through GDP measure).

Given this, for sustainability advocates to decide that the way to tackle that system is to do nothing about the direction of overall travel other than a little price adjustment just doesn’t seem to have much chance of success.

It’s like saying that the best way to tackle a river flowing in the wrong direction is to scoop out the occasional bucket from the stream and carry them to where we want to go, rather than engineering a diversion of the course of the river so that it reaches the required destination itself.

Some frontiers are not there to be crossed, but to be recognised and explored. The Monetary Frontier is a very valuable tool in reminding us that there is a point at which monetisation doesn’t help in delivering sustainability, and where price signals do not tell us anything useful for assessing direction.

Leave a Reply