Regulators, customers and consumers have increasing expectations regarding access to good quality, consistent information on sustainability, whether it is about a company’s overall performance, or about specific aspects of a product and how it compares to others. However, there’s a tension between the need to communicate and greatly increased scrutiny upon the quality and legitimacy of sustainability-related claims.

This article explores the context and what you need to consider while attempting to meet growing customer expectations and increasingly fierce regulators.

Introduction

This article is one of a series we have produced on the topic of greenwash. Our other pieces include an overview of why greenwashing matters and how to avoid it, and simple, practical advice for marketers.

Greenwashing – the practice of making claims about the environmental characteristics or performance of a product, process or institution without legitimate proof or context – is a growing problem.

Growing in two senses.

Firstly, there are major drivers to communicate. Because the sustainability agenda is rising in the consciousness of consumers and society, more companies want their customers to perceive them and their products in positive ways.

Secondly, the playing field is changing. As claims become more common (and arguably even more important) the validity of claims is receiving far greater scrutiny. Attention comes not just from sceptical consumers and NGOs, but also significantly from regulators in the UK and worldwide.

In the UK, an essential piece of the puzzle for addressing greenwashing is the publication, by the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) of the Green Claims Code (GCC).

The Green Claims Code consists of six fundamental principles which should apply to any environmental or sustainability claim.

These are as follows, green claims should:

- Be truthful and accurate.

- Be clear and unambiguous.

- Not omit or hide important relevant information.

- Compare goods or services in a fair and meaningful way.

- Consider the full life cycle of the product or service.

- Be substantiated.

The Green Claims Code has legal status, it’s not just a nice-to-have list. Its basis is in the consumer protection rules of the Consumer Protection from Unfair Trading Regulations 2008 (CPRs) and the Business Protection from Misleading Marketing Regulations 2008 (BPRs).

Both of these Regulations allow civil rights of address and criminal prosecutions. Crucially, an offence arising from the CPRs can potentially be attributed to the corporate body or an officer of the company.

Turning up the heat on claims

In July 2022, the CMA has demonstrated its intentions to enforce the GCC by launching an investigation into three fashion brands, ASOS, Boohoo and George at Asda.

In the words of the CMA’s interim chief executive, Sarah Cardell:

“We’ll be scrutinising green claims from ASOS, Boohoo and George at Asda to see if they stack up. Should we find these companies are using misleading eco claims, we won’t hesitate to take enforcement action – through the courts if necessary.”

The CMA’s focus upon greenwashing in fashion is prompted by the sector’s performance in complaints about green claims to the CMA.

Whilst the overall numbers of complaints are relatively low – 5 of 21 related to the fashion industry and focused on communications which related to issues like the use of recycled material in clothing and vaguer terms such as “sustainable manufacture”.

Fashion doesn’t quite top the CMA complaints table however. The most complaints the CMA received were about packaging (no. 1 on the list), with groceries at no. 3.

Other regulators in the UK and around the world are also stepping up their focus on greenwashing. For instance the UK Financial Services regulator, the FCA, published an open letter to its regulated firms in August 2022 which included a focus on ESG (Environmental, Social and Governance) related funds, which included the following instruction:

“Firms offering such [ESG] products should expect to be subject to review to ensure marketing materials accurately describe their product, with funds offering clear and consistent disclosure.”

The FCA has built upon the intentions outlined in the open letter with the release in late October 2022 of a series of proposed rules to tackle greenwashing – relating to the labelling and disclosure requirements of financial products, in order to address exaggerated or misleading claims. This reflects the focus and intentions of financial regulators across the world including the US, Australia, Singapore and Europe.

The FCA’s proposals include investment product label categories and clear limitations on where and how terms such as ‘ESG’, ‘green’ or ‘sustainable’ can be used.

With the launch of these proposed rules, Sacha Sadan, the FCA’s Director of Environment Social and Governance, said:

‘Greenwashing misleads consumers and erodes trust in all ESG products. Consumers must be confident when products claim to be sustainable that they actually are. Our proposed rules will help consumers and firms build trust in this sector.‘

Accuracy and context are key

Accurate communication doesn’t just refer to clarity, it is also about context, does a claim give rise to a misleading impression about overall corporate practice?

A recent example of a financial services firm falling foul of the regulators in relation to communicating the wider context of environmental communication was HSBC. The bank had a series of posters banned by the UK advertising watchdog the ASA (Advertising Standards Agency) because, while they focussed in some specific positive, climate-related activities of the bank, they failed to acknowledge the Bank’s overall role in wider emissions.

The ASA’s assessment and ruling makes interesting reading, it shows that the regulator examined a range of contextual sources of information from HSBC, including material in their Annual Report which provided details of the Bank’s overall portfolio of funding and holdings. The ASA’s conclusion was that:

“…we considered…. despite the initiatives highlighted in the ads, that HSBC was continuing to significantly finance investments in businesses and industries that emitted notable levels of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gasses. We did not consider consumers would know that was the case, and we therefore considered it was material information that was likely to affect consumers’ understanding of the ads’ overall message, and so should have been made clear in the ads.”

Messages with meaning – communicating complexity

A challenge with any claims about the environmental credentials of a product, service or organisation tends to be that buying pretty much anything is a worse environmental choice than not buying something.

This means that for any claim to be legitimate it needs to be relative, rather than absolute. For instance, rather than an absolute statement such as ‘sustainably produced’, a more credible statement would be a relative one, such as ‘produced with lower impacts than the average…’.

Such nuanced claims tend to be much less exciting from a marketing perspective than a more precise statement.

Another challenge is a practical one. When it comes to on pack messaging, there just isn’t much room for listing all the details, caveats, and links to underpinning scientific studies that would ideally be included to support a claim.

This is one of the reasons why eco-labels are so frequently used, where a recognised logo communicates something about the environmental/social credentials of a product in a quick and immediate manner.

The Green Claims Code Checklist (see below) allows scope to refer to information off-pack (information that really can’t fit into the claim can be easily accessed by customers in another way (QR code, website, etc.).

Avoiding greenwash – what to bear in mind

For companies wanting to communicate aspects of their approach, or of the performance of specific products and services, a detailed read of the Green Claims Code is essential, as is our simple guidance for taking the greenwash out of your claims. A copy of the Code and the supplementary 13-point Green Claims Code Checklist produced by the CMA should be constantly within reach of anyone responsible for corporate affairs, marketing, sales communication, and product packaging design.

In addition, there are choices to be made about the overall approach that you intend to take to communicating sustainability.

This could include not saying much! This might be either because you don’t have much to say, or that you are nervous about putting your head above the parapet. For those of you in the latter category, it can be valuable and legitimate to communicate what you don’t yet know but be clear about what you are going to do to find out.

Another thing to bear in mind is that, if you are going to make any relative claims about how a product is better either than other peoples’, or other ones in your range, you need to have a clear, transparent evidence base.

The best approach to such an evidence base is through the use of tools like LCA (life cycle analysis) or product and process footprinting, which can provide the ability to have definitive numbers, clear assumptions, boundaries and use cases.

Recognising this need, in March 2022 the European Union announced it’s intention to propose an LCA based methodology, called Product Environmental Footprint (PEF) to support a consistent approach to the evidence base for environmental claims.

However, it is also important to recognise where a specific number, of the sort that carbon footprinting can produce might be useful, but also when it doesn’t tell us the whole story. For some products, e.g. those derived from biological resources (food, raw materials etc), carbon performance is only one part of a larger picture, which should also include the ability to communicate information about farming/growing practice, biodiversity, labour issues etc.

If you are in doubt about any sustainability-related communication that you are planning, make use of the CMA Green Claims Code Checklist.

Remember that any good communication shouldn’t raise more questions than it answers and its always useful put yourself in the shoes of your most cynical critic and think about how they would receive and respond to your messages – and how you would respond to them.

Greenwashing – as regulators mobilise, what do marketers need to get right?

Greenwashing is insidious and widespread. It’s also harmful to your reputation, one of the main sources of value from taking meaningful action on sustainability issues.

And greenwashing is becoming a tidal wave.

So how should marketers and other professionals tackle this?

What is Greenwashing? Why it matters and how to avoid it

The need for meaningful change in business practice to deliver sustainability and equity is perhaps more pressing than ever. But persistent greenwashing undermines the wider understanding of sustainability, erodes trust, adds confusion and fuels cynicism.

Certified Greenwashing – Real Greenwash Kitemark

To-date, claiming environmental credentials has been somewhat of a niche activity. But now that consumers, governments and even a few companies are waking up to the power of blah blah blah – greenwashing really has gone mainstream.

There’s so much activity it can be difficult to keep up and not be overwhelmed with who’s claiming what and on what basis – or perhaps more importantly – what lack of basis.

It’s time to get professional. So, we’re pleased to announce the new Real Greenwash KitemarkTM.

Greenwashing – turning up the heat on green claims

Greenwashing is getting dangerous – regulators, customers and consumers have increasing expectations regarding access to good quality, consistent information on sustainability, whether it is about a company’s overall performance, or about specific aspects of a product and how it compares to others. This article explores the context and what you need to consider while attempting to meet growing customer expectations and increasingly fierce regulators.

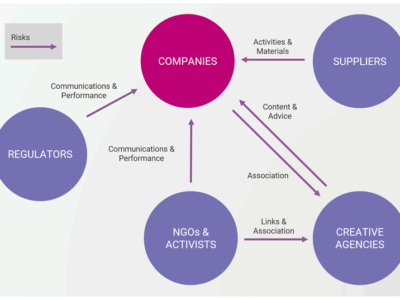

Greenwashing – dimensions of risk

Greenwashing – misleading communications on sustainability issues – has various dimensions of risk, but these are often overlooked, and their implications are insufficiently examined.

While greenwashing may appear as simply irritating, it actually causes a range of harm and presents multiple business risks. Risks to the company which communicates it – but also risks to companies involved in creating it and those associated with it.

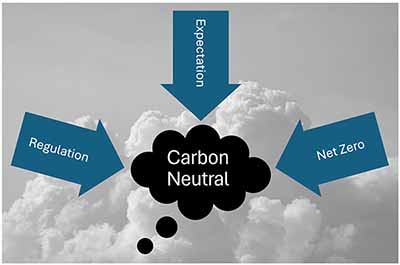

Carbon Neutral Communications

Despite considerable regulatory focus on carbon neutral claims, companies are still getting their communications wrong, so what is happening?

While many large companies now appear wary of making claims about carbon neutrality, we can still see considerable focus on these in the SME space, some fuelled by questionable labelling schemes.

This article reviews recent regulatory and best practice developments and explores where businesses have gone wrong.

ESG and Sustainability Reporting – are you engaging your investors?

ESG and Sustainability Reporting – are you engaging your investors?

Leave a Reply